Lecture Five:

Degeneracy, Culture,

and Critique

-

Part I:

Science, Reason,

and Knowledge I [DRAFT]

_________________________________

We have already staked out a wide

domain for the emergence of Cultural Studies even at this relatively

early point in this series of lectures. We have also, or at least I

hope we have also called into question not a few things that might

have been taken for granted or seemed “just the way the world is.”

The purpose of our introduction is not

to denounce or disavow the objects of our critique – though in

other contexts it might be appropriate to do both – nor is it to

give a special authority to Cultural Studies over other approaches

and formal disciplines. I hope that in the course of these lectures,

you will recognize that Cultural Studies is as much a cultural

artifact as are the objects of its analysis. It might appear that

academics such as myself are above the reach of the everyday, but a

quick reminder of Kant’s recognition of the Emperor’s power

should persuade you otherwise.

Understanding this point is in itself a

very good reason for asking you to view the two documentaries before

us, Michael Wood’s Hitler’s Search for the Holy Grail

and the PBS-style Degenerate Art.

Both of them illustrate the need to critique knowledge as well as

artistic production. They also set the stage for the first tendency

in Cultural Studies, the critical theory of the Frankfurt Institute

for Social Research [the “Frankfurt School”].

and holy and

wonderful being; but we must also inform him that in our State such

as he are not permitted to exist; the law will not allow them. And

so when we have anointed him with myrrh and set a garland od wool on

his head [‘tarred and feathered”], we shall send him away to

another city. For we mean to employ for our souls’ health the

rougher and severer poet or storyteller who will imitate the style of

the virtuous only, and will follow those models which we prescribe at

first when we began the education of our soldiers.” Plato,

Republic, Book III, 398.

And Socrates’ other student,

Xenophon, tells us that indeed one of the charges against Socrates

was that he had misused the poets to undermine the State: “...his

accuser alleged that he selected the most immoral passages, and used

them as evidence in teaching his companions to be tyrants and

malefactors....” Xenophon, Memorabilia, I. II., 53-57; pp.

39. Of course, as students of Socrates, each in their own way

defended him against the charges. Art effects the soul, whose care

has consequences for the State and was one of Plato’s chief

concerns in his Republic. Sorrowful or relaxing music as well

as flutes excepts those used by shepherds far from the city walls

would be banned in the Republic. Stringed instruments except

for the harp and the lyre would also be prohibited because “our

principle is that rhythm and harmony are regulated by the words, and

not the words by them.” Plato, Republic, Book III, 400.

“But shall not

our superintendence go no further, and are the poets only to be

required by us to express the image of the good in their works, on

pain, if they do anything else, of expulsion from our State? Or is

the same control to be extended to other artists, and are they also

to be prohibited from exhibiting the opposite forms of vice and

intemperance and meanness and indecency in sculpture and building

and other creative arts; and is he who can not conform to this rule

of ours to be prevented from practicing his art in our state, lest

the taste of our citizens be corrupted by him? We would not have our

guardians grow up amid images of moral deformity, as in some noxious

pasture, and here browse and feed upon many a baneful herb and flower

day by day, little by little, until they silently gather a festering

mass of corruption in their own soul. Let our artists rather be

those who are gifted to discern the true nature of the beautiful and

graceful; then will our youth dwell in a land of health, amid fair

sights and sounds,and receive the good in everything; and beauty, the

effluence of fair works, shall flow into the eye and ear, like a

health-giving breeze from a purer region, and insensibly draw the

soul from earliest years into likeness and sympathy with the beauty

of reason.

There can be no

nobler training than that, he replied. Plato, Republic, Book III, 401.

Certainly you find this idea of

committed art in, for example, Thucydides’ “Funeral Oration of

Pericles”

“When we do

kindness to others, we do not do them out of any calculations of

profit or loss: we do them without afterthought, relying on our free

liberality. Taking everything together, I declare our city is an

education to Greece.... Mighty indeed are the marks and monuments

which we have left. Future ages will wonder at us, as the present

age wonders at us now. We do not need the praises of a Homer, or of

anyone else whose words may delight us for the moment, but whose

estimation of facts will fall short of what is really there. For our

adventurous spirit has forced an entry into every sea and into every

land; and everywhere we have left behind us everlasting monuments of

good done to our friends or suffering inflicted on our enemies.”

(Thucydides, Peloponesian War, pp.119-120)

Pericles goes on to at the end implore

the wives and mothers of the dead to have and care for more children

so that they might replenish the ranks defending Athens. Where there

is a matter of the government of territory and population Art with a

capital A is never far behind. Who else designed and made all those

different kinds of uniforms, after all, so that soldiers might

recognize which territory and population that they each fought for.

And of course, the Greeks were not

alone in leaving their marks and monuments upon the landscape:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f1/Behistun_inscription_reliefs.jpg/1280px-Behistun_inscription_reliefs.jpg

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/12/RomeConstantine%27sArch03.jpg

At least Pericles admits that the

Athenian monuments serve an ideological purpose; they are “an

education to Greece.”

Be that as it may for the Classical era

– and we should always be careful not to read the present back onto

the past just to suit us – for the purposes of understanding our

era, we have to begin with the premise that education, ideology, and

knowledge are ineluctably linked to each other and each is as well an

aspect of Reason, the State, and the social relations of Capital.

What we call science, and what we say it establishes as true [or

rather knowledge] changes over time. Science is the human pursuit of

knowledge of the material world, and it changes as we change the

material world and are changed by it. There are, of course, many who

would take exception to this provisional definition, and you should

take their objections seriously. No one has all of the answers,

including myself. Socrates gave us that bit of wisdom, too.

The distinction is often made between

science and scientists, that error and bias reside with the

scientists, while science corrects such errors. It might even seem

as though if only we could have better people then we would

presumably have better science as the foibles and limitations of

humans would no longer stand in the way of scientific knowledge. It

is ironic that rather than separating science from scientists, those

who sympathize with such a view are readily admitting that science is

not separate from social relations, it is just that those scientists

and naturalists of the past are often seen as having been more

gullible, more prone to error and more likely to be susceptible to

the scientific ideologies of their day then we are in ours. This is

a version of saying that we are smarter now than they were then. A

little idea of progress is always sure to message the egos of any

contemporary, no matter the era in which they thrived.

Well, one thing we can say is that

those lesser beings of our past were quite often perfectly secure in

their knowledge that they were superior to their predecessors, too.

Cultural Studies should lead us to learn humility as we, like the

Angel Novus, are thrown forward rather than the hubris that

comes with an ideology of intellectual progress.

One could argue that science is a form

of rationalist and skeptical materialism and as such has a long

history. However, the institution of the laboratory and the figure

of the scientist are of relative recent invention.

Look at these two charts from Google,

which show the references in English to Scientist, scientist,

Laboratory, laboratory, Science, and science – it is unfortunately

case sensitive – from 1800 to 2008. Notice that the term scientist

appears rather late, as it is coined by William Whewell [

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Whewell ] in 1833 (he also gets

credit for the term “physicist,” too)

The distinction between scientists and

science also has the ultimate result of making science into something

metaphysical – another ironic aspect of the distinction – i. e.,

beyond the physical world. Making science into a metaphysical entity

(“a mysterious hieroglyphic” – to use Marx’s phrase) results

most importantly for our understanding of science, into the removing

of history and social relations. I suppose that is the point, since

the idea is to make science into something that is not effected by

the social or even, to a large degree, by its own history.

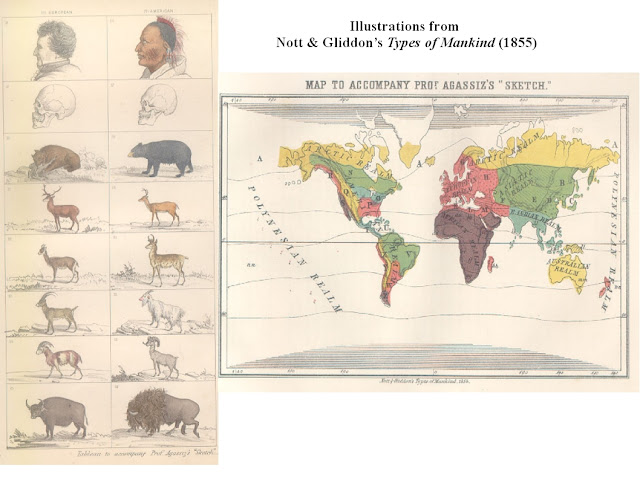

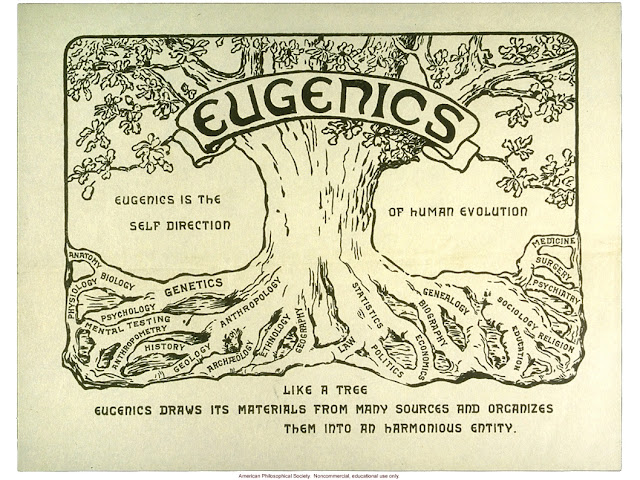

Remove science from the material of

society and history and you are left with a jaundiced science, but

also a science that might be adapted or adapt itself to any set of

historical social relations or reconciled with any history written

for the dominate ideology. Indeed, many of the errors of scientific

ideology that we would like to forget, such as the science of

Eugenics, were directed towards the government or populations and

territories.

To avoid this, one should try to see

science as having a history and this history is predominately a

history of errors, as George Canguilhem (Ideology and Rationality in the History of the life Sciences) has noted and W. P. D.

Wightman (Growth of Scientific Ideas,1951) affirmed: science

is “set in the context of the history of language & human

institutions of every kind.” After all, if science is a

self-correcting process, then even leaving aside the question of

social embeddedness for a moment, what is it correcting if not error

and what are today’s errors but yesterday’s truths? This is what

is really means to say that “science is a process.” Even the

term scientist did not exist until 1833. Was there “science’

before there were ‘scientists”? If not then science is a

relatively new invention for understanding the world and thus hardly

a candidate for being an eternal human pursuit. If the answer is

yes, then the history of science demonstrates that scientific

knowledge is conditioned by the contemporary structure of social

relations. Both views, however, leave open the possibility that

science as we know it is a product of the social transformations of

industrial society and the accompanying division of labor. Certainly

Whewell was thinking of the scientists as the embodiment of a new

rationalism.

But lets be clear that in critiquing

the authority of science we are not advocating irrationalism. Far

from it. The great materialist philosopher Epicurus responded to the

charge that he disavowed the gods by stating that it was not he who

insulted the gods, but those who affirmed the commonplace views of

the gods who truly insulted them. It is much the same with us. We

are taking science seriously, rather than degrading it by elevating

it to a metaphysical realm.

To emphasize the relation between

education, science, and ideology, I want to turn your attention to a

somewhat neglected series of events in the history of science that

Michael Wood introduces. Despite its unfortunate title, Wood shows

us how science and ideology can be linked and made to enhance the

authority of one enhances the authority of both. The documented

events are the context from which the Frankfurt School of Critical

Theory arose. It was in the midst of these and the events to be

described next week that Critical attention began to be given to the

artifacts of popular culture and everyday life.

Every successful revolution has

promoted some form of mass literacy, some grand reform of the

educational system. No matter whether the revolution was from the

left or the right. The Americans, the Soviets, the Cubans, the

Sandinistas, etc. all embarked on some form of literacy campaign.

After all, you need to be able to read the Constitution, Wall

Street Journal, Daily Worker, or whatever, for yourself.

So we should not be surprised when we take note of how central

education/knowledge was to the long-term goals of the Third Reich.

The emphasis on the purity and development of youthful bodies was not

at all discontinuous from this emphasis on knowledge. In fact, the

raising of youth for the new Reich demanded the strict regulation of

all aspects of education and knowledge, including science. What the

young German had to learn to become a National Socialist was all

important.

“For education

in the Third Reich, as Hitler envisaged it, was not to be confined to

stuffy classrooms but to be furthered by a Spartan, political and

martial training in the successive youth groups and to reach its

climax not so much in the universities and engineering colleges,

which absorbed but a small minority, but first, at the age of

eighteen, in compulsory labor service and then in service, as

conscripts, in the armed forces.... ‘The whole education by a

national state,’ he had written, ‘must aim primarily not at the

stuffing with mere knowledge but a building bodies which are

physically healthy to the core.’ But even more important, he had

stressed in his book the importance of winning over and then training

the youth in the service of ‘a new national state’ – a subject

he returned to often after he became German dictator. ‘When an

opponent declares, “I will not come over to your side,”’ he

said in a speech on November 6, 1933, ‘I will calmly say, “Your

child belongs to us already... What are you? You will pass on. Your

descendents, however, now stand in the new camp. In a short time

they will know nothing else but this new community.’” (Shirer.

[1950] 1960. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. p.343.)

Education was organized through the

reduction of the social status of teachers and professors except for

those who had already dedicated their careers to the study of Race

Science (Rassenkunde) or those who now embraced the view that

‘science, like every other human product, is racial and conditioned

by blood” (Shirer, p.345.)

“Every person in

the teaching professions, from kindergarten through the universities,

was compelled to join the National Socialist Teachers’ League

which, by law, was held ‘responsible for the execution of the

ideological and political coordination of all teachers in accordance

with National Socialist doctrine.’ The Civil Service Act of 1937

required teachers to be ‘the executors of the will of the

party-supported State’ and to be ready ‘at any time to defend

without reservation the National Socialist State.’ An earlier

decree has classified them as civil servants and thus subject to the

racial laws. Jews, of course, were forbidden to teach. All teachers

took an oath to ‘be loyal and obedient to Adolf Hitler.’ Later,

no one could teach who had not first served in the S. A., the Labor

Service, or the Hitler Youth. Candidates for instructorships in the

universities had to attend for six weeks an observation camp where

their views and character were studied by Nazi experts and reported

to the Ministry of Education, which issued licenses to teach based on

the candidates political ‘reliability.’” (Shirer. [1950] 1960.

The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. p.344)

See also:

[Karl] Barth is SuspendedProfessor Refuses to Take Fealty Oath to HitlerThe Montreal Gazette - Nov 27, 1934.http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=838uAAAAIBAJ&sjid=PZkFAAAAIBAJ&pg=2175%2C3377821

Heidegger is in the middle of the photo as he was on his way to give his first address as Rector of

the university in 1933. https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhj6nJIOarKxTs8bN391VpVo8beJzboJugdNoP4NRk3MwiUhN8SN_WEkNKD_3aq8TX55fi2qtiGRgLiLaJ2eNU2qBK7npUaLPoEFKwCIfk6Hy_Ezx9KAFlWoTQSCVjTbW_J_RW5YC-V/s1600/Rektor.jpg

We might assume that universities were

centers of liberalism. Certainly the common view of modern American

academia is of a bastion of liberalism or even radicalism. In

neither case is this commonplace view correct. In reality, it

depends on the specific field and department. Yes it is more likely

that a sociology professor will be a liberal than a professor of

business administration, but there are far more professors of

business or engineering than there are professors of sociology.

Then, of course, there are those professors that imagine themselves

to be liberal or radical when they actually espouse conservative

positions. (For example, one commonly hears from a vocal few that “I

am a Marxist (or radical, or anarchist or committed to one or another

identity-based ‘new politics’)” and that is used to justify an

opposition to being unionized. In the old days one would hear the

call for Black separatism, which would have in fact only served to

reinforce the system of segregation that gripped America. The

examples are many. So to see the university or academics as liberal

or radical is to simply and conveniently ignore the obvious.

Universities are inherently conservative institutions where the vast

majority of students and faculty are to be found in so-called

apolitical or technical fields (e.g., engineering, medical, computer

science, forensics, etc.) or in fields that tend to affirm the

current status quo of social relations (law, business, sports,

architecture, etc.). The Frankfurt School itself owed its existence

to a wealthy philanthropist who funded it because there was no space

for them in the conventional university. It was affiliated with the

university, but was largely separate. The only other similar

institution would have been the Bauhaus, and in fact they were

created within a couple of years of each other and there was a good

deal of personal and intellectual exchange between them.

Ludwig

Mies van der Rohe designed the monument to Rosa Luxemburg and Gropius was close to Alban Berg,

Adorno’s friend and teacher. Berg’s Violin Concerto (To

the Memory of an Angel) was composed as a memorial to Gropius’

and Alma Mahler’s recently deceased 18 year-old daughter, Manon.

Anton Webern perhaps because he was too upset by Berg’s own death

in December 1935 to conduct the premiere in April 1936, but conducted

the U. K. premiere of the work only a couple of months later.

Leonid Kogan plays Alban Berg's violin

concerto.

There are many other connections, and

these connections were as much due to the fact that both institutions

were quite marginal during their day and became more so as the

authoritarian movement grew until those that could fled the

continent.

“The Wiemar

Republic had insisted on academic freedom, and one result had been

that the vast majority of university teachers, anti-liberal,

undemocratic, anti-Semitic as they were, had helped to undermine the

democratic regime. Most professors were fanatical nationalists who

wished the return of a conservative, monarchical Germany.... By 1932

the majority of students appeared to be enthusiastic for Hitler.

It was surprising

to some how many members of the university faculties knuckled under

to the Nazification of higher learning after 1933. Though official

figures put the number of professors and instructors dismissed during

the first five years of the regime at 2,800 – about one fourth of

the total number – the proportion of those who lost their posts

through defying National Socialism was, as Professor Wilhem Roepke,

himself dismissed from the university of Marburg in 1933, said,

‘exceedingly small.’ Though small, there were names famous in

the German academic world: Karl Jaspers, E.I. Gumbel, Theordor Litt,

Karl Barth, Julius Ebbinghaus and dozens of others. Most of them

emigrated, first to Switzerland, Holland, and England and eventually

to America.... A large majority of professors, however, remained at

their posts, and as early as the autumn of 1933 some 960 of them, led

by such luminaries as Professors Sauerbach, the surgeon, Heidegger,

the existentialist philosopher, and Pinder, the art historian, took a

public vow to support Hitler and the National Socialist regime.

‘It was a scene

of prostitution,’ Professor Roepke later wrote, ‘that has stained

the honorable history of German learning.’” (William Shirer.

[1950] 1960. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, p.347)

“The new Nazi

era of German culture was illuminated not only by the bonfires of

books and the more effective, if less symbolic, measures of

proscribing the sale or library circulation of hundreds of volumes

and the publishing of many new ones, but by the regimentation of

culture on a scale which no modern Western nation had ever

experienced. As early as September 22, 1933, the Reich Chamber of

Culture had been set up by law under the direction of Dr. Goebbels.

Its purpose was defined, in the words of the law, as follows: ‘In

order to pursue a policy of German culture, it is necessary to gather

together the creative artists in all spheres into a unified

organization under the leadership of the Reich. The Reich must not

only determine the lines of progress, mental, and spiritual, but also

lead and organize the professions.’”

“Seven

subchambers were established to guide and control every sphere of

cultural life: The Reich chambers of fine arts, music, the theater,

literature, the press, radio and the films. All persons engaged in

these fields were obligated to join their respective chambers, whose

decisions and directives had the validity of law. Among other

powers, the chambers could expel – or refuse to accept – members

for ‘political unreliability,’ which meant that those who were

lukewarm about National Socialism could be, and usually were,

excluded from practicing their profession or art and thus deprived of

a livelihood.... Every manuscript of a book or a play had to be

submitted to the Propaganda Ministry before it could be approved for

publication or production. (William Shirer. [1950] 1960. The

Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, pp. 333-334.)

“After six years

of Nazification the number of university students dropped more than

one half – from 127,920 to 58,325. The decline in enrollment at

the institutes of technology, from which Germany got its scientists

and engineers, was even greater – from 20,474 to 9,554.” (William

Schirer. [1950] 1960. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich,

pp.347-348)

But those who espoused the creation of

a German science were the extreme; less obvious still are those that

simply went along so as to either further their own careers or their

scientific fields (which no doubt in the long run would also be

personally beneficial). Some of these were swept up in the social

movements of the time, while others went about work which tellingly

could fit within the structures of either the Wiemar Republic or the

Third Reich.

Shirer may be forgiven for his

denunciation of the professors. He had witnessed the rise of

National Socialism as a reporter in Berlin and other European

capitals; interviewed most of the major and minor figures in the

years before the declaration of war between the United States and

Germany, covered the war as a combat reporter, and continued his work

during the post-war period. He was the first reporter picked by the

legendary Edward R. Murrow to work for CBS News. His radio reports

are just as notable as his later work with Edward R. Morrow (

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_L._Shirer )

A documentary of the book was made

(something that would not happen today!) and you can view it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sfjm9Ic-Ric

As a witness to the book burnings of

May 1933, Shirer reminds us that the bonfires took place not in some

Nazi cellar or stadium rally, but “opposite the University of

Berlin” after “a torchlight parade of thousands of students.”

(Shirer, p.333) you’ve seen clips of that night and you see

glimpses of them in both documentaries. Shirer relates that some

twenty thousand books were burned that night in Berlin and at rallies

in several other cities. He gives a partial list of the authors

whose works were put to the torch:

“Thomas Mann,

Heinrich Mann, Lion Feuchtwanger, Jakob Wassermann, Arnold and Stefan

Zweig, Erich Maria Remarque, Walther Rathenau, Albert Einstein,

Alfred Kerr, and Hugo Preuss, the last named being the scholar who

had drafted the Weimar Constitution....Jack London, Upton Sinclair,

Helen Keller, Margaret Sanger, H. G. Wells, Havelock Ellis, Arthur

Schnitzler, [Sigmund] Freud, [Andre] Gide, [Emile] Zola, [ ] Proust.

In the words of a student proclamation, any book was condemned to

the flames ‘which acts subversively on our future or strikes at the

root of German thought, the German home, and the driving forces of

our people.’” (William Schirer. [1950] 1960. The Rise and

Fall of the Third Reich, p.333.)

If we had time we would look at the

chapter “The Misunderstood Poet” from Brent Engelmann’s

Everyday Life in Nazi Germany to get even more of an

understanding of how the burnings were no mere propaganda/media

events, but indicative of the changes in everyday life that many –

if they were not of a suspect class or degenerate stock – were

rapidly adjusting themselves to accommodate. Christopher Isherwood

was in Berlin during the same period as Shirer and so they give us

two nicely parallel artifacts of the era. Isherwood writes in his

Berlin Stories how much had changed during the years he taught

English in Berlin. Thugs from the SA, the forerunner of the SS, now

stood about accosting passersby and acting as moral police. One of

Isherwood’s students who had been a police chief under the Wiemar

regime took his lessons in the semi-secrecy in his car as his driver

toured them about or as they walked in a park or countryside.

Isherwood recorded various encounters and like all urban dwellers,

snatches of everyday life as he strolled the streets:

“Overheard in a

cafe: a young Nazi is sitting with his girl; they are discussing the

future of the Party. The Nazi is drunk.

‘Oh, I know we

shall win, all right,” he exclaims impatiently, ‘but first blood

must flow!’

The girl strokes

his arm reassuringly. She is trying to get him to come home. ‘But,

of course, it’s going to flow, darling,’ she coos

soothingly, ‘the Leader’s promised that in our Programme.’”

(Isherwood, The Berlin Stories, p.199)

In the chapter “Winter 1932-33”

“This morning as

I was walking down the Bulowstrasse, the Nazis were raiding the house

of a small liberal pacifist publisher. They had brought a lorry and

were piling it up with the publisher’s books. The driver of the

lorry mockingly read out the titles of the books to the crowd: ‘Nie

Wieder Krieg!’ he shouted, holding up one of them by the corner

of the cover, disgustedly, as though it were a nasty kind of reptile.

Everyone roared with laughter.

‘No More War!’

echoed a fat, well-dressed woman, with a scornful, savage laugh.

‘What an idea!’” (Isherwood, The Berlin Stories,

p.205.)

[This incident may be related to the closing and sacking of the Anti-War Museum in Berlin, which occurred in March of 1933 and the work by Ernst Friedrich, who founded the museum, War Against War. It is one of the most noted works in the pacifist/anarchist tradition. Be forewarned that the images in War against War are very disturbing. Friedrich wanted to convey the horror of war, much like Otto Dix, but with photographs of disfigured and crippled soldiers, military executions, and the aftermath of battle. ‘Nie Wieder Krieg! was the slogan of the pacifist movement in the interwar period. see http://www.anti-kriegs-museum.de/english/history.html]

Shortly after witnessing the sacking of

the office, Isherwood decided to leave Berlin for good. He relates

that when he informed Frl. Schroeder, who boarded him,

“She is

inconsolable: ‘I shall never find another gentleman like you, Herr

Issyvoo – always so punctual with the rent . . . . I’m sure I

don’t know what makes you want to leave Berlin, all of a sudden,

like this. . . .’

It’s no use

trying to explain to her, or talking politics. Already she is

adapting herself, as she will adapt herself to every new regime.

This morning I even heard her talking reverently about ‘Der Fuhrer’

to the porter’s wife. If anybody were to remind her that, at the

elections last November, she voted communist, she would probably deny

it hotly, and in perfect good faith. She is merely acclimating

herself, in accordance with a natural law, like an animal which

changes its coat for the winter. Thousands of people like Frl.

Schroeder are acclimating themselves. After all, whatever government

is in power, they are doomed to live in this town.”

(Isherwood, The

Berlin Stories, pp.206-207.)

Isherwood would later become a member

of the circle of Americans and European exiles in Los Angeles that

included Mann, Schoenberg, Adorno, Brecht, Weill, Eisler, etc. The

Berlin Stories, really two novelistic memoirs, were published in

1935 and 1939. You know some of it in a more popular form as the

basis for the musical Cabaret.

Shirer and Isherwood witnessed the

consolidation of the authority of the new regime. What struck both

of them was the degree to which the residents of Berlin quickly

acclimated themselves to the new regime. Shirer noted the effects on

himself of the relentless repetition of the ideology across the

realms of education, entertainment, culture, and knowledge. Indeed,

the Authoritarian impulse to merge all of these under the rubric of

the State was satisfied for a time.

“I myself was to

experience how easily one is taken in by a lying and censored press

and radio in a totalitarian state. Though unlike most Germans I had

daily access to foreign newspapers, especially those of London, Paris

and Zurich, which arrived the day after publication, and though I

listened regularly to the BBC and other foreign broadcasts, my job

necessitated the spending of many hours a day in combing the German

press, checking the German radio, conferring with Nazi officials and

going to party meetings. It was surprising and sometimes

consternating to find that notwithstanding the opportunities I had to

learn the facts and despite one’s inherent distrust of what one

learned from Nazi sources, a steady diet over the years of

falsifications and distortions made a certain impression on one’s

mind and often misled it. No one who has not lived for years in a

totalitarian land can possibly conceive how difficult it is to escape

the dread consequences of a regime’s calculated and incessant

propaganda. Often in a German home or office or sometimes in a

casual conversation with a stranger in a restaurant, a beer hall, a

cafe, I would meet with the most outlandish assertions from seemingly

educated and intelligent persons. It was obvious that they were

parroting some piece of nonsense they had heard on the radio or read

in the newspapers. Sometimes one was tempted to say as much, but on

such occasions one was met with such a stare of incredulity, such a

shock of silence, as if one had blasphemed the Almighty, that one

realized how useless it was even to try to make contact with a mind

which had become warped and for whom the facts of life had become

what Hitler and Geobbels, with their cynical disregard for truth,

said they were.” (William Shirer. [1950] 1960. The Rise and

Fall of the Third Reich, p.342.)

Into and from this mix come the

human-all-too-human academics, scientists, and naturalists of the

Ahnenerbe to affirm the ideology of the regime and the

scientific ideologies of race and culture, to locate the origins and

true nature of the Indo-European/Germanic volk and thus affirm

their destiny as well.

This is a good place to break before we

go on. An appropriate piece of music to hear before the second part

is this, Oliver Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time (1941)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UeSVu1zbF94

A work for clarinet, violin, cello and piano by Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992), who composed the piece while being held prisoner by the Germans during the Second World War. The quartet was premiered by clarinetist Henri Akoka, violinist Jean le Boulaire, cellist Étienne Pasquier and Messiaen on the piano in Stalag VIII-A in Görlitz, Germany (now Zgorzelec, Poland) on Jan. 15, 1941, before an audience of about 400 prisoners and guards.

Käthe Kollwitz, Lithograph, Gefangene, Musik Horend

(Prisoners Listening to Music), 1925.

Canguilhem, Georges. 1988 [1977]. Ideology and Rationality inthe History of the Life Sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Engelmann, Bernt. 1986. In

Hitler’s Germany: Everyday Life in the Third Reich. New York:

Pantheon Books.

Gueriin, Daniel. 1973 [1965] Fascism

and Big Business. New York: pathfinder Books.

Isherwood, Christopher. 1935-1939.

The Berlin Stories. New York: New Directions.

Isherwood, Christopher. 1938. The Berlin Stories (The Last of Mr. Norris and Goodbye to Berlin. New York: New Directions.

Plato. 1892. The Dialogues of Plato translated into English with Analyses and Introductions by B. Jowett. Humphrey Milford: Oxford University Press.

Poulantzas, Nicos. 1974 [1970].

Fascism and Dictatorship: The Third International and the Problem of

Fascism. New York: Verso Books.

Shirer, William. 1960 [1950]. The

Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. New

York: Fawcett Crest.

Thucydides. 1954. The Peloponnesian War. New York: Penguin Classics.

Toland, John. 1976. Adolf Hitler.

New York: Ballantine Books.

Wightman, William P. D. 1951. The Growth of Scientific Ideas. New Haven: Yale University Press.

_________________________________

Next:

Degeneracy, Culture, and Critique - Part I: Science, Reason, and

Knowledge II